View sample communication research paper on gender and communication. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

TV talk shows such as Oprah frequently feature experts on communication between the sexes; self-help books promise to teach readers the secrets of communicating with “the opposite sex”; and popular magazines such as Essence, Cosmo, and Sports Illustrated routinely include articles on how to attract, interact with, and hold the attention of the man/woman of your dreams. People are fascinated by how women and men communicate, especially how their communication differs.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Likethegeneralpublic,academicresearchersareinterested in gender and communication. Since the 1970s, scholars have focused great attention on gender and communication. As a result, we now know a great deal about the ways in which sex and gender shape communication styles and, in turn, how our communication reinforces social views of women and men. One of the most important understandings to grow out of research is that we can become more informed and effective communicators if we understand the pivotal role that gender plays in both personal and cultural life.

Studying gender and communication heightens our awareness of taken-for-granted notions of sex and gender that are deeply woven into the social fabric and that we’ve been encouraged to accept. Once we become aware of these notions and think about them critically, we are empowered to accept those we find good or useful in a more informed way than we had. Equally important, becoming informed about gender empowers us to dispute conventional views of the sexes that we don’t find desirable or admirable. Sometimes, we challenge and resist social definitions of gender on an individual level—for instance, a man who chooses to be a stay-at-home dad instead of a primary breadwinner or a woman who is aggressive and domineering. We may also challenge and attempt to change social views of gender on a broader level—for instance, arguing as some women in the 1800s did that women are rational enough to vote or contesting the long-standing practice of not allowing women in the U.S. armed services to be in combat roles.

In this research paper, we’ll discuss what we know about gender and communication and why it matters to us individually and to our society. The first section of the paper provides definitions of three interconnected terms: sex, gender, and communication. In the second section, we examine how we develop gendered patterns of communicating and what language features are associated with feminine and masculine communication styles.

Understanding Sex, Gender, and Communication

Many people use the words sex and gender interchangeably, but actually they are discrete concepts. As we’ll see, the distinction between sex and gender calls our attention to the twin influences of biology and society—or nature and nurture—on our identities.

Sex

Sex is a biological category—male or female—that is determined genetically. Most individuals are designated as male or female based on external genitalia (penis and testes in males, clitoris and vagina in females) and internal sex organs (ovaries and uterus growth and muscle mass are controlled by chromosomes and hormones. Most humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, one of which determines sex. Typically, those people society labels male have XY sex chromosomes, and those that society labels female have XX chromosomes.

You may have noticed that I’ve used words such as most and typically when discussing sex. That’s because there are variations from the most common patterns. For instance, some individuals classified as female have XO or XXX sex chromosomes, and some individuals classified as males have XYY or XXY chromosomes. Furthermore, intersexed individuals don’t fit into the binary categories of male or female. They are born with the biological qualities of both sexes—for instance, internal sex organs characteristic of females and external genitalia characteristic of males. Transsexuals who have undergone hormone treatment and surgery may have some features and aspects of appearance that are not consistent with their sex chromosomes.

Gender

Gender is a more complicated concept than sex. In the 1970s, researchers began to draw a clear distinction between sex and gender. They defined gender as a social construction, which contrasts sharply with sex as a biological phenomenon. Understanding gender as socially constructed allows us to realize that views and expectations of masculinity and femininity grow out of specific historical moments and specific cultural contexts. Put another way, gender is the social meaning attached to sex within a particular culture and in a particular era. Gender influences the expectations and perceptions of women and men, as well as the roles, opportunities, and material circumstances of women’s and men’s lives.

Because gender is central to social order, society works very hard to convince us that its definitions and expectations of women and men are natural, normal, and right. From birth, most of us are socialized into our society’s views of what it means to be a man or woman—what each sex should and should not do. Pervasive practices reflect and aim to reproduce social definitions of gender: pink and blue blankets, which are still used in many hospitals and home nurseries; toys marketed to boys (active, adventure toys) and girls (dolls and play stoves); chores parents typically assign to sons (outdoor tasks) and daughters (indoor tasks); kindergarten and elementary teachers’tendencies to allow boys to play rougher and be less attentive than girls are expected to be; workplace norms that make it acceptable for female but not male workers to take parental leave.

It’s important to realize that studying gender involves learning about both femininity and masculinity. Gender is often perceived as a synonym for women or women’s interests. Just as the study of race is mistakenly, but commonly, perceived not to have anything to do with Caucasians, the study of gender is routinely perceived as having nothing to do with men and masculinity. However, Western culture recognizes two genders, and some other cultures recognize more than two. Masculinity is just as socially constructed as femininity. Understanding how and why masculinity has been constructed as it has helps us understand how many men define themselves and which attitudes and behaviors they do and do not consider appropriate for themselves. Studying gender helps us understand the processes by which each and all genders are constructed and—by extension—the ways in which existing constructions of each and all genders might be challenged and changed.

Beyond Gender as a Social Construction: A Performative Framework

By the late 1980s, many researchers found that defining gender as socially constructed didn’t accomplish as much as they had originally thought. Although scholars still agreed that societies develop and advance particular views of femininity and masculinity, many came to believe that the social construction of gender is only part of the story and not the most interesting part. In 1987, Candice West and Don Zimmerman asserted that gender is not something people have (a personal quality) but rather something they do. Following this insight, Judith Butler (1993) argued that there is nothing “normal” or “natural” about gender. She rejected the widely held view that gender exists prior to particular actions. Instead, claimed Butler, gender comes into being only as we perform it in everyday life. We simultaneously enact and produce gender through a variety of mundane, performative practices, such as dress, gestures, and verbal acts, that embody—and, thus, confer an illusory realness on—normative codes of masculinity and femininity. In other words, for Butler and other performative theorists, gender is more appropriately regarded as a verb than as a noun. Gender is doing; without doing (without the action of performance), there is no gender.

We express, or perform, conventional gender through everyday practices such as dominating (masculine) or deferring (feminine) in conversations, offering solutions and judgments (masculine) or empathy (feminine) when a friend discloses a problem, and crossing our legs so that one ankle rests on the knee of our other leg (masculine) or so that one knee rests over the other knee (feminine). Conversely, we resist conventional views of gender if we act in ways that are inconsistent with the sex and gender society assigns to us.

But our performances of gender are not solo enterprises. They are always collaborative because however we express gender, we do so in a context of social meanings that transcend any individual. For instance, a woman who defers to men and tilts her head when talking to men (two behaviors deemed feminine and more often exhibited by women than men), is acting individually, yet her individual actions are stylized performances of femininity that are coded into cultural life, and it is precisely because these actions are coded and understood as feminine that a person performing them is perceived as feminine. Our choices of how to act in any given moment are based on, and are in response to, a social world made up of other people who are either physically in the context or mentally present through our imagining of them.

Viewing gender as performative has three important implications. First, it leads to the realization that gender exists if and only if people act in ways that compel belief in the reality of masculinity and femininity and thereby fortify belief in that reality. Second, the argument that gender is not objective or natural implies that any gendered identity is as real (and as illusory) as any other. Thus, transvestites, gays, transsexuals, lesbians, bisexuals, and intersexed and transgendered people have sexual and gender identities that are as real—or unreal—as those of heterosexuals. Third, because a performative view of gender recognizes a range of genders, sexes, and sexualities, it undermines the conventional binary categories of male/female, masculine/ feminine, gay/straight, and normal/abnormal. Because the performative view of gender, sex, and sexuality profoundly challenges conventional understandings of identity, it is powerful in opening up new questions about cultural values, beliefs, and definitions.

Communication

The third concept we will discuss is communication. Communication is a dynamic process of creating meaning through verbal and nonverbal symbols. Communication is related to sex and gender in a number of ways, four of which we’ll discuss here.

Communication Socializes Us Into Gendered Identities

First, communication is a primary means by which new members of a society are taught existing views of gender.As parents interact with children, they teach gender. Boys may be discouraged from playing with dolls, and girls may be scolded for getting dirty—both messages that convey social views of gender in an effort to teach children how to perform identities that are consistent with existing social norms.

Parents are not the only ones who communicate society’s views and expectations of gender. Siblings, other relatives, peers, and teachers talk differently to boys and girls and give positive and negative responses to children’s behaviors. Operating from conventional assumptions about appropriate behaviors for the sexes, a teacher may scold a girl who is raucous in first grade but allow a boy in the class to act up. Peers are likely to ridicule a boy who is scared of rough play; they may call him “sissy” or “mama’s boy” in an effort to shame him into following norms for masculine behavior.

Media too socialize children into gendered identities by providing models of masculinity and femininity. Research shows that children’s television programs tend to feature male characters who have active roles and female characters who have reactive or supporting roles. In both programs and advertising, girls are more likely than boys to be shown nurturing others (including pets and dolls), and boys are more likely to be shown engaging in adventures and risk. Video games and movies also provide models of masculinity and femininity, thereby helping socialize children into gender roles approved by Western culture.

Communication Expresses Gendered Identities

Second, as performative theorists assert, we use communication to express, or perform, gender.We know which clothes will be seen by others as masculine or feminine; we understand which postures are regarded as appropriate and inappropriate for women and men; we realize that certain words and tones of voice are regarded as more acceptable for men and others as more acceptable for women. In other words, we use verbal and nonverbal communication to “do gender.”

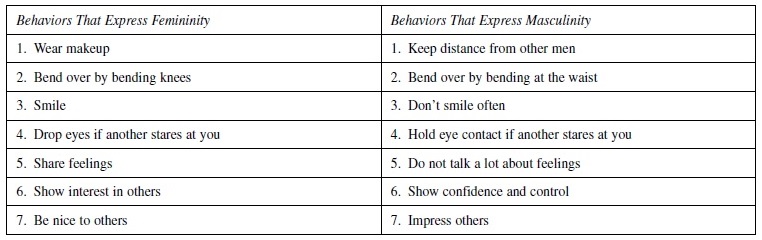

Recently, I asked my students to give examples of behaviors that they perceive as expressing femininity or masculinity. Table 1 below presents a sample of the examples they gave.

Table 1. Behaviors That Express Femininity or Masculinity

Communication Challenges and Changes Social Views of Gender

Third, communication is a key means of changing gender. We can use communication to challenge existing views of men’s and women’s nature, behaviors, and rights. For example, the movement for women’s suffrage, which began in the 1800s, included nonverbal (marches) and verbal (speeches, written documents) communication that challenged and ultimately changed the view that women were not entitled to rights such as voting, owning property, and pursuing higher education. Today, there are a number of fathers’ groups that are challenging entrenched views that women are “natural” caregivers and so should have custody of children when parents split up. Senator Hillary Clinton’s campaign to be the Democratic nominee for president challenged the view that women cannot run for president. We also challenge existing views of gender by engaging in transgressive everyday practices. Some of my students queer the binary categories of gender by, for instance, wearing a lacy dress and combat boots or skirts, heels, and a necktie.

Communication Names Issues and Identities

Finally, communication enacts naming, which is a critical means of making issues related to gender visible. We name things that we consider important and don’t name things that we don’t consider important. When we name phenomena that have not been named, noticed, or valued, we bring those phenomena into social awareness. Once we had names only for heterosexuals and homosexuals. The term homosexual was challenged, and today it is used less often than gay and lesbian, which are different ways of naming identities. Furthermore, we have named categories of sexual identity beyond the original two. Coining terms such as bisexual, queer, trans, and intersexual has named into social awareness identities that were previously unnamed and, therefore, largely unrecognized.

Communication can also name issues into social consciousness. Consider five phenomena related to gender and gender roles that once were not named but now have been named and, thus, brought into social awareness.

In a book that is credited with instigating the second wave of feminism in the United States, Betty Friedan (1963) called attention to “the problem that has no name.” Friedan divided this problem into two parts. First, many middle-class stay-at-home mothers felt frustrated and not completely fulfilled because their lives were restricted to the home and family. Second, because the ideology of the time maintained that they were living the American dream, many of these women felt guilty for not feeling fulfilled and grateful. Friedan decided to name the problem; she called it the feminine mystique—the ideology that being a full-time homemaker was the ideal and the only ideal for women. When she gave a name to something that was common in women’s experience but unmarked in language, Friedan gave visibility and social standing to what had been invisible and, thus, had no social legitimacy.

Sexual harassment is unwanted and unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature that interferes with performance in work and educational settings. Doubtlessly, sexual harassment has existed for centuries, yet it was not named until the 1970s. Until that time, people, primarily women, who endured unwanted sexualized behavior at work and in school had no way to name what happened to them. The language of their culture provided no language that named the practice as illegal, much less immoral. Now that the term sexual harassment is part of our language, there is a way to name this experience for what it is.

Like sexual harassment, date and marital rape are not new phenomena. However, naming these practices as criminal acts—rape—is new. Only toward the end of the 20th century did most states adopt laws that specifically recognized nonconsensual sex between dates or spouses as the crime of rape. And only by naming nonconsensual sex in any context as a crime were the grievous violations recognized for what they are.

The sociologist Arlie Hochschild (2003) used the term second shift to name a phenomenon common in the lives of women who work outside of the home.The second shift is all the housework, cooking, and child care that women engage in after returning from a shift in the paid labor force. Hochschild reported that roughly 20% of men in dual-worker couples assume half of the work required to run a home and family. More recent studies have confirmed the persistence of inequity in responsibility for work in the domestic sphere. In naming this phenomenon as a form of work, the term second shift gives visibility to what had been invisible.

The second shift involves more than concrete tasks such as preparing dinner, bathing children, and vacuuming. In addition, it includes what Hochschild dubbed psychological responsibility, which is the responsibility to remember, plan, schedule, and so forth. For example, behind a prepared dinner sitting on a table are a number of generally unseen and unnoticed tasks such as considering household members’nutritional needs and dietary preferences, deciding on a menu, and shopping for the necessary ingredients.

Let’s summarize what we’ve discussed so far. This first section of the paper defined sex, gender, and communication. In the process, we highlighted the ways in which communication is related not only to individuals’ gender but also to social understandings of gendered identities and issues. Our exploration of these three terms should give you a preliminary sense of how complex they are and should spark your thinking about the intimate ways in which gender shapes communication and, in turn, is shaped by communication. We turn next to a review of knowledge about gender and communication in our lives.

Gendered Communication Patterns

Male and female infants don’t enter the world communicating in different ways. However, within just a few years, boys and girls do start engaging in some distinct communication behaviors. Many factors influence children’s development, including their development as communicators. We’ll focus on two particularly important influences on the development of gendered communication patterns: parents and peers.

Parents

Parents are an early and powerful influence on most children’s understandings of gender. Perhaps most obviously, parents are typically models of masculinity and femininity. By observing parents, children often learn the roles socially prescribed for women and men. In heterosexual families that adhere to traditional sex roles, children of both sexes are likely to learn that women are supposed to nurture others, clean, cook, and show emotional sensitivity and that men are supposed to earn money, make decisions, and be emotionally controlled.

Parents’ behaviors are another key influence on children’s development of gendered identities and communication patterns. Although many parents today reject rigid sex stereotypes, many still communicate differently with sons and daughters and encourage, however inadvertently, distinct communication behaviors in sons and daughters. Typically, girls are rewarded for being cooperative, helpful, nurturing, and deferential—all qualities consistent with social views of femininity. Parents may also reward— or at least not punish—girls for being assertive, athletic, and smart. For boys, rewards are more likely to come for behaving competitively, independently, and assertively.

Ethnicity is related to parental gender socialization. Research shows that middle-class Caucasian parents in the United States emphasize and encourage achievement more when talking to sons than to daughters, and some Chicano/Chicana families discourage educational achievement in daughters to the point of regarding daughters who attend college as Chicana falsa—false Chicanas. On the other hand, Asian and Asian American families tend to encourage high achievement in children of both sexes.

Parents also convey distinct messages about assertiveness and aggressiveness to sons and daughters. As children, boys and girls don’t differ a great deal with respect to feelings of anger or aggression. Because of gender socialization, however, they learn different ways of expressing those emotions. Research shows that parents, particularly white middle-class parents, tend to reward verbal and physical activity, including aggression, in sons and to reward interpersonal and social skills in daughters. Because many girls are discouraged from direct, overt aggression yet still feel aggressive at times, they develop other, less direct ways of expressing aggression, such as those featured in the film Mean Girls.

Parents, especially fathers, encourage in children what they perceive to be gender-appropriate behaviors, fostering more independence, competitiveness, and aggression in sons and more emotional expressiveness and gentleness in daughters. When interacting with children, fathers tend to talk more with daughters and to engage in activities more with sons. Mothers tend to talk more about emotions and relationships with daughters than with sons. Because both mothers and fathers tend to talk more intimately with daughters than sons, daughters generally develop greater relational awareness and emotional vocabularies than sons.

However, the general patterns for family interaction do not hold true for all families. In some families, sons are socialized to be emotionally aware and expressive. For example, a student of mine named Vince is very emotionally expressive—he hugs male friends and talks openly about feelings. As we were discussing family communication in my class, Vince noted that his family is Italian and they live in an Italian neighborhood. He pointed out that, as a group, Italians tend to be more expressive and emotional than many ethnic groups.

In general, parental gender socialization is more rigid for boys than for girls, particularly in Caucasian families, and fathers are more insistent on gender-stereotyped toys and activities, especially for sons, than are mothers. Fathers generally regard it as more acceptable for girls to play baseball or football than for boys to play house or cuddle dolls. Similarly, it’s considered more suitable for girls to be strong than for boys to cry and more acceptable for girls to act independently than for boys to cling to others for support. The overall pattern is that parents, especially fathers, more intensively and rigidly push sons to be masculine than they push daughters to be feminine.

Peers

Peers have at least as much and perhaps more influence than parents on our identities and communication styles. A classic study by Daniel Maltz and Ruth Borker (1982) gave us initial insight into the importance of children’s play in shaping patterns of communication. The researchers noticed that young children tended to play in sex-segregated groups, and groups of girls and groups of boys generally played different kinds of games. These two observations have been confirmed by more recent research.

The games that boys typically played included football, baseball, basketball, and war, whereas the games that girls tended to play included school, dolls, and house. Students in my classes have added to these lists, noting that boys’ games also include cops and robbers and soccer and girls’ games include tea party and dress up. The games noted by Maltz and Borker, as well as those added by my students, operate by quite different rules and cultivate distinct communication styles.

The games that boys typically play involve fairly large groups—nine individuals for each baseball team, for instance. Most boys’ games are competitive, have clear goals (touchdown, basket, capturing the robbers or evading the cops), involve physically rough play (blocking linebackers, shooting robbers), and are organized by rules (nine innings to a baseball game, two points per basket) and roles (forwards shoot baskets, guards protect forwards) that specify who does what and how to play.

Because the games boys typically play are structured by goals, rules, and roles, there is limited need to discuss how to play, although there may be talk about strategies to reach goals. In playing games, boys learn to communicate to accomplish goals, compete for and maintain status, exert control over others, get attention, and stand out. Specifically, boys’ games cultivate four communication rules:

- Use communication to assert your ideas, opinions, and identity.

- Use talk to achieve something, such as solving problems or developing strategies.

- Use communication to attract and maintain others’ attention.

- Use communication to compete for the “talk stage.” Make yourself stand out; take attention away from others, and get others to pay attention to you.

These communication rules are consistent with other aspects of masculine socialization. For instance, notice the emphasis on individuality and competition. Also, we see that these rules accent achievement—doing something, accomplishing a goal. Boys learn that they must do things to be valued members of the team. Finally, we see the undercurrent of masculinity’s emphasis on invulnerability: If your goal is to control and to be better than others, you cannot let them know too much about yourself and your weaknesses.

Quite different patterns exist in games typically played by girls, and they cultivate distinct ways of communicating. Girls tend to play in pairs or in very small groups rather than large ones. Also, games such as house and school do not have preset, clear-cut goals and roles. There is no touchdown in playing house, and the roles of daddy and mommy aren’t fixed like the roles of guard and forward. Because traditional girls’ games are not highly structured by external goals and roles, players have to talk among themselves to decide what to do and what roles to play.

When playing, young girls spend more time talking than doing anything else—a pattern that is not typical of young boys. Playing house, for instance, typically begins with a discussion about who is going to be the daddy and who the mommy. The lack of stipulated goals for the games is also important because it tends to cultivate girls’ skill in interpersonal processes. The games generally played by girls teach four basic rules for communication:

- Use communication to create and maintain relationships. The process of communication, not its content, is the heart of relationships.

- Use communication to establish egalitarian relations with others. Don’t outdo, criticize, or put down others. If you have to criticize, be gentle.

- Use communication to include others—bring them into conversations, respond to their ideas.

- Use communication to show sensitivity to others and relationships.

The typically small size of girls’ play groups fosters cooperative discussion and an open-ended process of talking to organize activity, whereas the larger groups in which boys usually play encourage competition and external rules to structure activity. Research on preschoolers found that boys gave orders and attempted to control others, whereas girls were more likely to make requests and cooperate with others. In another investigation, 9- to 14-yearold African American girls typically used inclusive and nondirective language, whereas African American boys tended to issue commands and compete for status in their groups. The bottom line is that girls tend to engage in more cooperative play, whereas boys tend to engage in more instrumental and competitive play.

Masculine and Feminine Communication Among Adults

The lessons of children’s play are carried forward. The basic rules of communication that many adult women and men employ are refined and elaborated versions of those learned in childhood games.

Feminine Communication

Extensive research has identified seven features of feminine communication, which a majority of women employ. As we discuss them, think about how these features might grow out of the games typically played by young girls. First, feminine communication involves disclosing personal information and learning about others. For many women, personal communication is the primary means of building close relationships.

Second, feminine communication attempts to create equality between people. Instead of vying for MVP (most valuable player) status, women are more likely to communicate in ways that level the playing field. To create equality, women often offer matching experiences (“I’ve experienced the same thing”) and downplay their individual accomplishments. In addition, women tend to work to include others and keep the conversation balanced so that participation is relatively equal.

Third, feminine speech tends to offer substantial support for others. In conversations, women routinely express sympathy, empathy, and agreement with others (“Of course, you feel hurt,” “I know just how you feel,” “I think you handled that really well”). In addition, women often communicate support by showing interest in learning more about others and their experiences (“How did you feel when that happened?” “Is this experience connected to earlier ones in your relationship?”). All these conversational behaviors demonstrate interest in others and concern for how others feel and what happens in their lives.

A fourth feature of feminine communication is doing what Pamela Fishman (1978), in a classic article, labeled “conversational maintenance work.” This is the process of keeping a conversation going by inviting others to speak, asking questions that draw others into interaction, responding to what others say, and encouraging others to elaborate their ideas. Rather than working to get and hold the talk stage for themselves, women who enact feminine communication are more likely to invest in getting everyone on the talk stage.

Fifth, feminine communication tends to be highly responsive, especially nonverbally. Women exceed men in eye contact during conversations, head nodding, and facial expressions that show interest, as well as verbal responses that demonstrate engagement in others and what they are communicating.

Sixth, feminine communication tends to include more concrete descriptions and ideas than masculine communication. Women typically include details when describing events and experiences and provide specific examples to illustrate abstract ideas. In addition, women are more likely than men to cite personal experiences as bases for broad judgments and values.

Finally, feminine communication tends to be more tentative than masculine communication. Women are more likely to use hedges (“I sort of think that plan is dangerous”), qualifiers (“I don’t have a lot of experience with this issue, but . . .”), and tag questions (“The weather is really nice, isn’t it?”). Although the tentativeness of feminine communication has been criticized for being unassertive and powerless, it is also inclusive, leaving the door open for others to enter the conversation.

Masculine Communication

Researchers have identified six features of masculine communication, which are employed by a majority of men. As you read about these, you’ll probably notice that the features are cultivated by the games that young boys typically play. The first feature of masculine communication is control or the effort to control. Many men see interaction as an arena for pitting themselves against others and proving their worth. The effort to control is displayed by asserting opinions, challenging others, and telling stories and jokes that capture others’ attention.

A second feature of masculine communication is instrumentality, which is accomplishing objectives. As a rule, males use communication to manage tasks—to do something. In interaction, instrumentality is expressed through problem solving, giving advice, devising strategies, and developing plans. In contrast to the attention to feelings and process that is typical of feminine communication, masculine style puts greater emphasis on facts and results.

Third, masculine communication tends to be used to express dominance and control. Although there are many jokes about women’s talkativeness, it is actually men who talk more in most contexts. Overall and across interaction contexts, males—both boys and men—talk more often and for longer periods of time than females—both girls and women. In addition, men are more likely than women to reroute conversations to their interests and agendas and to interrupt others to exert control over interaction and to maintain command.

Fourth, masculine communication tends to be direct and assertive. In contrast to the tentativeness of feminine communication, the masculine style tends to be more forceful, authoritative, and confident. In addition, masculine communication tends to be more direct, absolute, and unqualified than feminine communication.

Fifth, masculine communication is more abstract than feminine communication. Men rely less than women on concrete examples, specific experiences, and concrete reasoning. Instead, men often talk at abstract levels, relying on generalizations and conceptual levels of description. For example, a man might note that Barack Obama is

“politically progressive,” which is an abstract and general phrase. A more concrete observation would be that Barack Obama voted against the war in Iraq and for legislation to provide support for children.

A final feature of masculine communication is restricted emotionality. In general, men’s speech is less emotional, and they disclose less about feelings, fears, concerns, and personal thoughts than women. In addition, men tend to be less emotionally responsive to others’communication. By extension, they are less likely than women to express sympathy, empathy, or other feelings in response to what others say.

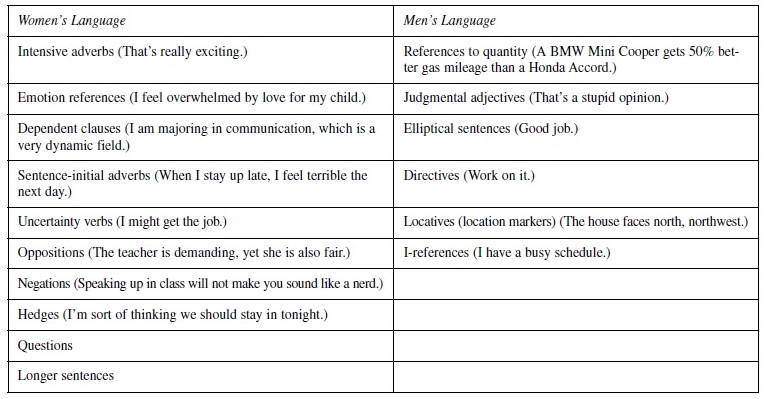

Anthony Mulac (2006) recently studied women’s and men’s language to see whether the differences noted in earlier research still exist. Based on his findings, Mulac stated that women and men “grew up in different sociolinguistic cultural groups, groups that have subtly different styles and therefore subtly different ways of accomplishing the same communicative task” (p. 236). Note that Mulac calls these “subtly different styles,” which is a more nuanced and accurate description than offered by some popular advice book authors who claim that women and men are so different, they are from different planets. Mulac identified 6 distinctive characteristics of men’s use language and 10 distinctive characteristics of women’s language. As you consider Mulac’s findings, which are summarized in Table 2, ask how each characteristic fits with the features of women’s and men’s communication that we have just discussed.

Table 2. Women’s and Men’s Use of Language

Qualifying Research Findings

Before we conclude this discussion of gendered patterns of communication, I want to emphasize the limits of what research can tell us. Research on gendered styles of communicating provides us with generalizations about how women and men, in general, communicate in a specific cultural context. It cannot tell us how any particular individual will communicate. Some men communicate in primarily feminine ways, and some women communicate in primarily masculine ways. As we saw in the example of Vince, ethnicity interacts with gender to shape communication style. Men who are socialized in expressive ethnic communities are likely to be more emotionally expressive than men who are not. Likewise, women who are socialized in emotionally inexpressive ethnic groups tend to be less emotionally expressive than women who are socialized in Western feminine speech communities.

We should also note that most people—regardless of sex and gender—engage in some masculine and some feminine communication behaviors. If you compare your own verbal and nonverbal behaviors with the descriptions of masculine and feminine communication we’ve discussed in this research paper, you’ll probably discover that your communication includes some features that are classified as feminine and some that are classified as masculine. Very few of us communicate in solely masculine or solely feminine ways.

Finally, what is considered masculine and feminine communication varies across cultures and over time. For this reason, what is regarded as masculine in the United States might be feminine or androgynous in another culture. Also, what is considered feminine or masculine today might have been perceived otherwise in a different era. For example, it is not uncommon today for males to wear earrings or necklaces. In the 1800s, a man who wore such jewelry would have been seen as inappropriately feminine.

Conclusion

In this research paper, I introduced you to an area of research and teaching that has fascinated me for more than 20 years. In the first section of the paper, I defined key concepts—sex, gender,andcommunication—andthenexaminedhowresearchers have thought about each one and its relation to the other two. The second section of the paper focused on gendered styles of communication. We traced the influence of family and peers on children’s development of gender identity and, by extension, gendered patterns of communication. We also considered specific features of masculine and feminine communication that researchers have identified.

What we’ve covered in this research paper tells us only what gender means in our society today. What it can or will mean in the future is an open question and one that you will take part in answering. Each of us is part of the ongoing process of constructing gender, communication, and culture. Each of us affects what they are and will be.

Bibliography:

- Andersen, M., & Collins, P. H. (Eds.). (2007). Race, class, and gender: An anthology (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

- Ashcraft, K., & Mumby, D. (2004). Reworking gender: A feminist communicology of organization. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Breines, W. (2006). The trouble between us: An uneasy history of white and black women in the feminist movement. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Butler, J. (1993). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, J. (2004). Undoing gender. London: Routledge.

- DeMaris, A. (2007). The role of relationship inequity in marital disruption. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24, 177–195.

- Dindia, K., & Canary, D. (Eds.). (2006). Sex differences and similarities in communication (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Dow, B., & Wood, J. T. (2006). The SAGE handbook of gender and communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Fishman, P. M. (1978). Interaction: The work women do. Social Problems, 25, 397–406.

- Fixmer, N., & Wood, J. T. (2005). The political is personal: Difference, solidarity, and embodied politics in a new generation of feminists. Women’s Studies in Communication, 28, 235–257.

- Friedan, B. (1963). The feminine mystique. New York: Dell.

- Hochschild, A. (with Machung, A.). (2003). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home (Rev. ed.). New York: Viking/Penguin Press.

- Kailey, M. (2006). Just add hormones: An insider’s guide to the transsexual experience. Boston: Beacon.

- Lamb, S., & Brown, L. (2007). Packaging girlhood: Rescuing our daughters from marketers’ schemes. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Maltz, D. N., & Borker, R. (1982). A cultural approach to malefemale miscommunication. In J. J. Gumperz (Ed.), Language and social identity (pp. 196–216). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Messner, M. (2007). Masculinities and athletic careers. In M. Andersen & P. H. Collins (Eds.), Race, class, gender: An anthology (6th ed., pp. 172–184). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

- Metts, S. (2006). Hanging out and doing lunch: Enacting friendship closeness. In J. T. Wood & S. W. Duck (Eds.), Composing relationships: Communication in everyday life (pp. 76–85). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Monsour, M. (2002). Women and men as friends: Relationships across the life span in the 21st century. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Monsour, M. (2006). Gendered communication in friendships. In B. Dow & J. T. Wood (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of gender and communication (pp. 57–70). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mulac,A. (2006). The gender-linked language effect: Do language differences really make a difference? In K. Dindia & D. Canary (Eds.), Sex differences and similarities in communication (pp. 219–239). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Pitcher, K. C. (2006). The staging of agency in Girls Gone Wild. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 23, 200–218.

- Schechter, T. (2005). I was a teenage feminist: A documentary about redefining the F-word [Film]. Cambridge, MA: (www.trixiefilms.com)

- Sloop, J. (2006). Critical studies in gender/sexuality and media. In B. Dow & J. T. Wood (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of gender and communication (pp. 319–333). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Steiner, L. M. (2007). Mommy wars: Stay-at-home and career moms face off on their choices, their lives. NewYork: Random House.

- West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender and Society, 1, 125–151.

- Wood, J. T. (2006). Gender, power and violence in heterosexual relationships. In D. Canary & K. Dindia (Eds.), Sex differences and similarities in communication (2nd ed., pp. 397–411). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wood, J. T. (2010). Gendered lives: Communication, gender, and culture (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage.

- Wood, J. T., & Inman, C. (1993). In a different mode: Recognizing male modes of closeness. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 21, 279–295.