View sample anthropology research paper on social relationships. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

This research paper describes the importance of support systems such as family, friends, communities, and religious groups. Such support systems form the core of an individual’s social network. Anthropologists are interested in these relationships and how information flows through networks. Along with this, we will describe the history and major current uses of social network analysis (SNA) in anthropological research, as well as introduce common barriers to the effective use of SNA. These obstacles include ethical and power issues that come into play with some forms of SNA research. We conclude with a discussion of diverse anthropological case studies that used SNA methodology, pulling from the diverse contexts of nonprofit organizations, business, early childhood development, medical anthropology, and even primatology.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Social relationships form between two or more people through interactions. It is these complex, and often symbolic, interactions with other people that make us distinctly human. The entire discipline of anthropology is concerned with social relationships of some sort. To give a description of how linguists, cultural anthropologists, biological anthropologists, and archaeologists study social relationships is a daunting and formidable task. However, SNA is proving to be a powerful methodology for many anthropologists, as well as diverse groups of other social scientists.

SNA is one of many methodologies used to study and analyze groups of people, be they individuals, organizations, communities, or even countries. This methodology analyzes whether a relationship exists between these units, called nodes, and places a value on that relationship. SNA is not a new technique and has been in use since the early 1930s. However, its usage has increased over the past 20 years as a valuable tool for anthropologists, economists, sociologists, planners, program evaluators, and those in the corporate world, among other researchers. Social network analysis is particularly well suited for understanding complex systems and relationships, as it depicts systemic elements and their interactions to form a complex whole. By identifying the individuals interconnected, a researcher can also identify leaders or those developing as leaders. It is for this reason that SNA has become so valuable in the business world.

Social networks are formed in society through contacts in many aspects of daily life. While most people think of a social network as a collection of people that they know socially, it is more than just personal friendships and connections. Social networks include the people we know professionally—through work, school, and volunteerism. This extends to the people that our friends and relatives know as well. Such networks can be studied from the perspective of identification of the network, effectiveness, and meaning.

Social network analysis research focuses on two types of social networks: sociocentric and egocentric networks. Sociocentric networks aim to depict the relationships among members of an entire group. Anthropologists may use this form of analysis to study clubs, classrooms, or entire villages. The purpose of sociocentric network analysis is to understand the structure of the group and how it relates to individual or group behavior or perceptions. Egocentric networks consist of the relationships of an individual. The respondent, called ego, names the people he knows and the social network is mapped out. Egocentric data enable the researcher to study social support networks, the relationship between disease and certain helpseeking behaviors, and many other interpersonal interactions.

A factor aiding the popularity of the SNA methodology is the availability of computer software that helps create sociograms to facilitate analysis. A sociogram is a visual display of the individuals (nodes) and their connections. These connections encompass a wide range of relationships, such as communication ties, formal ties, kinship ties, and proximity ties. These ties are visually distinguished from each other, and the length of the ties indicates the social distance between individuals. The most popular SNA software is UCINET because it is continually updated and provides many forms of data manipulation and network methods and tools. Additionally, this software is robust and capable of handling large amounts of data for numerous individuals, such as for sociocentric analyses. Other network data analysis software programs include Egonet, NetMiner, STRUCTURE, NetDraw, FATCAT, JUNG, and StOCENET.

The anthropological use of SNA can be viewed in direct contrast to traditional anthropological research. Instead of the key informant, individual-centered ethnography, SNA assumes that all actors are linked in an intricate latticework of social relationships, affecting their worldview and influencing their behaviors. Understanding these relationships at a deeper level delves into the realm of sociology and social psychology in terms of viewing people as groups of social beings. Anthropologists are becoming more concerned with understanding structural relations because they are often more valuable in describing behaviors than demographic characteristics like age, sex, and religious beliefs. People’s social relationships vary widely depending on the circumstances of the different environments in which they interact; people have an ability to “status shift.” That someone can be a quiet individual at work and an outspoken member of his or her community gives testimony to the fact that these relationships cannot be explained by demographics, since that individual retains those demographic characteristics regardless of the social context. Anthropologists are still conducting traditional ethnographies and engaging in SNA, which adds to the breadth of the discipline.

History of Social-Network Analysis

Long before the term social network analysis was coined, there were examples of its use. This begins with Lewis Henry Morgan’s analysis of kinship of the Iroquois. In the mid-19th century, Morgan’s League of the Iroquois (1851) detailed and diagramed kinship of the six nations that composed the Iroquois Federation. In fact, many early anthropologists recognized the importance of kinship in the societies that they were studying. Anthropologists then began to study kinship extensively and use diagrams to represent relationships. However, SNA is not an exclusive tool of anthropologists and can be found in use in many disciplines including sociology, psychology, mathematics, information technology, business, political science, and the medical field.

Formal social-network studies were developed in two social science fields independently of one another. Psychotherapist Jacob L. Moreno is credited with developing sociometry around 1932, a quantitative method for measuring social relationships, and the sociogram, the tool for representing these relationships. At this time, sociometry was used by psychologists and consisted of investigating who was friends with whom in order to explore how these relationships served as limitations and/or opportunities for action and for their psychological behavior (Scott, 2000). Although social scientists had spoken of webs or networks of people, it was Moreno’s invention to use spatial geometry to graphically represent these relationships in a sociogram. People were “points” and relationships were “lines” and people were placed closer together or farther apart based on the strength of their relationship. This makes it immediately apparent upon viewing a sociogram who the individuals were and how they were related. Moreno’s gestalt orientation toward psychotherapy led him to investigate how mental health is related to the social networks to which people belong.

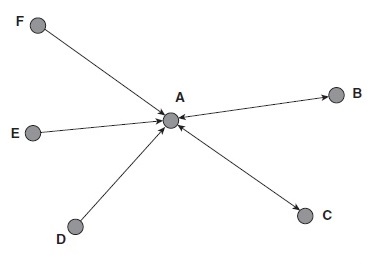

Moreno recognized its utility in identifying well-connected people and how information flowed through a group. He coined the term sociometric star to refer to the important leaders that were able to influence many others in the network. In Figure 1, the sociometric star is the friend choice of everyone in the network, yet individual A only chooses two individuals as friends.

Moreno also studied these microlevel personal interactions and SNA to infer the basis of large-scale social aggregates, which included interaction with the economy and the state (Moreno, 1934). Shortly thereafter, psychologist Kurt Lewin, pioneer of social psychology and action research, picked up on this study of group behavior as a series of interactions with the environment that could be studied mathematically using vector theory and typology in the mid-1930s. Lewin (1951) aimed to mathematically explore the interdependence between the group and the environment as a system of relations. Lewin’s early work in SNA brought him close to what would later develop into systems theory. In 1953, Cartwright and Harary (1956) pioneered graph theory applications to group behavior that drew on Lewin’s use of mathematical models for group behavior. Their use of SNA was also characterized by an important shift in thinking about group behavior. These models facilitated a shift in thinking of cognitive relationships existing in people’s minds to the understanding of interpersonal balance in social groups. This allowed researchers to build models of the interdependence among the different individuals’ views and attitudes in a group (Scott, 2000, p. 12).

Around the same time, anthropologists Alfred RadcliffeBrown, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and also Émile Durkheim posited their views that the main purpose of social, or cultural, anthropology was to identify social structures and the formal relationships that connect them, and that this could be accomplished with discrete mathematics. They began investigating subgroups within social networks and ways to identify these subgroups from relational data. Another important development at this time was the way in which relational data was obtained. Social scientists began using anthropological observation methods to record and diagram the formal and informal relationships of people within networks.

In the 1950s, Manchester University’s department of social anthropology began focusing not on group cohesion, but on group conflict and how social relationships affect not just the individuals involved, but the society as a whole (Scott, 2000, p. 26). This placed emphasis on not only the relationships, but also the nature of those relationships, a fundamental tenet of SNA. The Manchester anthropologists were unable to record their findings in the simplistic kinship diagrams of their field, and so turned to RadcliffeBrown and others for the use of SNA. Anthropologist Harrison White, of Harvard University, is credited with further developing the mathematical and schematic nature of SNA in the 1960s and 1970s, which allowed notions like social role to be mapped and measured.

The development of SNA tells us much about how the different social science fields can use this methodology to achieve their goals. Although different researchers have different backgrounds and theoretical orientations, Scott (2000) states that SNA is especially valuable because it does not mandate a specific theoretical framework (p. 37).

SNA can be thought of as a series of methods instead of a theoretical orientation; however, all researchers engaging in SNA are attempting to reveal the structure of societies or social groups. SNA is well suited to uncover social structures, predict the emergence of leaders and relationships, and represent these relationships graphically.

Support Systems

The dynamic of the family creates a social network that uses the power of shared DNA and marriage as the basis of forming a support system through kinship. This system is further expanded through friendship, adoption, and godparentship. In looking at the social network of kinship as a support system, clues are given by the terms used between members to describe their relationships, and by the frequency of contact between them. For example, an individual may consider the relationship with a cousin stronger than that with a cousin twice removed, regardless of any difference in the biological relationship. A survey of the members of a kinship group to determine the terms used and the frequency of contact between members can identify the support system within the larger context of the complete kinship group.

Support networks can also be found in neighborhoods, care facilities, education systems, and workplaces. Jacobson’s (1987) work on the support systems found in elder care facilities looks at the meaning of social support as a framework for analyzing the network. A spontaneously organized breast cancer self-help group is the subject of study into how consensus is used to negotiate belief systems and knowledge (Mathews, 2000). The support network found in the agricultural society of Madagascar looks at how the network contributes to the economic system (Gezon, 2002).

Each of these studies examines very different types of support systems from various angles, showing good examples of the depth and breadth of the possibilities for finding support systems. The viewpoint of each of these studies shows the manner in which a network can be viewed, whether from the viewpoint of the families, as in the elder care facilities, or the members who formed the network, as in the self-help group. The final example of the economic system in Madagascar views the network from the viewpoint of those who are on the fringe of the network rather than the central members. This is much like a discussion involving kinship where determining who is ego is important to determine the relationships to that individual.

Current Trends in SNA

Popular uses of SNA extend to the creation of online communities such as MySpace, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Spoke as SNA gains popularity and momentum. Greatly increased access to personal computers has expanded the available tools to more easily analyze and create networks. The current popularity of SNA among the public can be traced to the game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon.” This actor has appeared in such a wide variety of films throughout his career that it is possible to connect him to any other actor through the films that they have in common. For example, actress Sophie Marceau was in The World Is Not Enough with Pierce Brosnan, who was in The Thomas Crown Affair with Rene Russo, who was in Major League with Tom Berenger, who was in Gettysburg with Sam Elliott, who was in Tombstone with Bill Paxton, who was in Apollo 13 with Kevin Bacon, for six degrees.

Other current trends in SNA are in researching organizational structure, nonprofits, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Provan and Milward (2001) define a network as “a collection of programs and services that span a broad range of cooperating by legally autonomous organizations” (p. 417). They go further to point out that there are “network administrative organization(s)” that facilitate networking by the distribution of funds (p. 418). Examples of network administrative organizations include the United Way and Community Shares. Both of these organizations raise funds and subsequently distribute funds to nonprofit organizations. This often places them at the center of a network of nonprofit organizations.

Provan and Milward’s (2001) work examines the effectiveness of networks between organizations providing public services. They argue that “networks must be evaluated at three levels of analysis: community, network, and organization/participant levels” (p. 414). One point made by Provan and Milward is that the boundaries of a community in a discussion of community-based networks do not necessarily follow geographic boundaries (p. 416).

The discussion of nonprofit organizations in Europe is the basis of Fowler’s 1996 work. This discussion takes into consideration the larger network of “economic, political, social, ecological, and other systems” that NGOs are situated within (p. 60). It is important to understand that nonprofit organizations and NGOs do not create exclusionary networks. They operate within the context of governments, businesses, the general public, and the people they service. Fowler’s analysis shows these as a linear equation. However, the network of nonprofit organizations as shown by Lind (2002) shows that this network is not linear in that the participants and volunteers in many cases overlap to create less of a straight line and more of a circular configuration. It is this overlap that creates the basis for a power structure.

The “dramatic change in the division of responsibility between the state and the private sector for the delivery of public goods and services” (p. 1343) is the focus of Besley and Ghatak’s work (2001). They look at the arrangements between these entities and the need for analysis to discern who should be responsible for the delivery of public goods and services. Besley and Ghatak go into a detailed mathematical model to determine the value of the investments made in the delivery of public goods and services. They explain as follows:

Any discussion of NGOs is further complicated by the fact that they have not only increased in number and taken on new functions, but they have also forged innovative and increasingly complex and wide-ranging formal and informal linkages with one another, with government agencies, with social movements, with international development agencies, with individual INGOs (international NGOs), and with transnational issue networks. (Besley & Ghatak, 2001, p. 441)

This is another acknowledgment of the network that exists between nonprofit organizations. Fisher (1997) makes a call in this paper for “detailed studies of what is happening in particular places or within specific organization[s]” (as cited in Besley & Ghatak, 2001, p. 441). One caution made by Fisher is that “NGOs are idealized as organizations through which people help others for reasons other than profit and politics” (as cited in Besley & Ghatak, 2001, p. 442). Something that benefits one person or group may have an adverse effect on another person or group.

Power Issues and Ethics

Riner’s (1981) look at the networks created by corporations describes the concept of membership on multiple boards, or connections through directors, as interlocking. Riner states, “Interlocking occurs when an individual serves simultaneously as a member of two or more of these boards.

Directorate interlocking connects individual decision-making components in a global network which may be considered the core institution of fifth-level organization” (p. 167). The literature suggests that this interlocking is one of the levels, the fifth level, of networking that links organizations to each other by showing the links of key people—volunteers, staff, and board members—in both current and historical positions. Riner also discusses interlocking in relation to what was termed by Pratt in 1905 as a business senate that controls the United States (p. 168). This echoes C. Wright Mills’s (1999) assertion in The Power Elite that it is the power elite who are actually in control, rather than the elected government. Mills’s theory states, “They [the power elite] are in positions to make decisions having major consequences” (p. 4). Riner’s work defines and describes interlocking in reference to corporate boards. One of the case studies in the following section applies this concept to the boards of nonprofit organizations to establish the existence of a social network in Cincinnati.

Yeung’s (2005) work looks not at the network itself, but at the meaning of the relationship that forms the network; by looking at only the network without analyzing the meaning of the relationship, the cultural meaning of the relationship is lost (p. 391). Fisher (1997) quotes Milton Friedman as saying that “the power to do good is also the power to do harm” (p. 442). Something that benefits one person or group may have an adverse effect on another person or group. It is clear that these aforementioned authors have done groundbreaking work on power and power networks. However, power can also be misrepresented in data collected for SNA. A number of research studies have investigated the respondent bias in egocentric analyses (see Romney & Weller, 1984) and have concluded that people often overestimate their centrality when they are asked to self-report their social networks (Johnson & Orbach, 2002, p. 298). Whether by intentional deceit or accidental oversight, researchers have found, people’s responses and their actual behaviors often have little overlap. Researchers also learned that an individual’s response accuracy depends on the frequency of the respondent’s interactions and the long-term behavior patterns the respondent had directly observed in the group. Johnson and Orbach have found that as individuals are more familiar with, and knowledgeable of, their networks, the smaller their “ego bias.” Studies have also concluded that selfreported power relationships may be biased based on the respondent’s centrality, social rank, and reputation in the group (Krackhardt, 1990).

Another danger that appears in SNA is the loss of subject anonymity. Despite the anthropologists’ attempts to conceal the names of their informants, the nature of a social network lends itself to the ability of anyone familiar with the network in question to identify the informants based on their reported connections. This becomes an issue especially in cases of applied anthropologists working in a corporate setting. Many times, corporations use SNA to study the structure and efficiency of their business. Employees may be required to participate in the study by their employer with the understanding that their responses will be kept confidential. However, many times the nature of the answers can be easily attributed to an individual or department. Further, the results of SNA can be used to determine policies that may affect jobs, hiring, and promotions.

Case Studies

Social-network studies are used by many professionals and appear in a wide variety of research journals and publications. This cross-cultural discipline continues to evolve as researchers share and borrow across their respective fields. The following case studies provide a brief glimpse into the ways anthropologists have used SNA methodology to study nonprofit organizations, business, health, kinship, and even primatology.

Nonprofit Social Networks

Anthropologists do not always study the individual, or egocentric networks. The diversity of the field of anthropology results in the ability of anthropologists to study larger entities, such as organizations, institutions, and even networks of entire countries. In The Seven Degrees of Cincinnati: Social Networks of Social Services, Stambaugh (2008) diagrammed the structure of nonprofit organizations to show the connections created through key people: board members, employees, and volunteers. In this study, three groups were charted showing three distinct socialnetwork structures. The first group, civic organizations located in the uptown area of Cincinnati, showed a distinct center of power based on the proportion of connections to other nonprofit organizations. The assumption of power was further confirmed from a financial angle by comparing the annual income of the civic organizations through publicly available tax returns. Additional evidence of the amount of power held by this organization was seen in the organizations it represented. The organization, the Uptown Consortium, was formed by an alliance of the five major employers in uptown, each of which is also a nonprofit organization.

Additional analysis of these organizations shows that they have connections to another 198 organizations through funding or shared real estate. The projects undertaken by the Uptown Consortium benefit the five organizations that formed it, rather than the communities in which they are located. This causes some tension between the community councils that represent each of the seven communities in uptown, and the Uptown Consortium. Essentially, this has created two separate and competing communities in uptown; the daytime community of commuting workers and the nighttime community of residents.

The second case study looks at the relationship between the Cincinnati City Council and the 51 community councils recognized throughout the city. There are 52 communities that make up Cincinnati, each with a distinct personality. What distinguishes this case study from the uptown example is the lack of connections of key people creating centralized power. This example has 23 community councils with connections to other nonprofit organizations, leaving 28 community councils with no apparent interlocks. Also, the nature of a community council requires that the members must live in the community, which precludes membership on more than one community council. With the exception of the community councils located in uptown, there appears to be little linking the community councils to each other apart from some secondary connections. This lack of connections diffuses the potential power of the community councils, leaving it with the city council.

The third case study looks at nonprofit youth organizations located in Cincinnati beginning with the Great Rivers Girl Scout Council and the Boy Scouts of America, where we would expect to find connections to other youth-based organizations. What is striking about this case as opposed to the uptown case is that the youth organizations do not appear to be connected to similar organizations. This creates a network that moves money into these two youth organizations, but not to other youth-based organizations that could become the basis for a power network.

Social Networks in Business Anthropology

Using SNA in business anthropology tends to be more straightforward than other anthropological uses. In business and organizations, managers and senior leaders are concerned with networks and relationships that affect their employees’ workflow. Usually, managers believe they understand such relationships, but they are often not aware of certain informal work relationships. Krackhardt and Hanson (1993) argue that it is these informal networks that have the greatest effect on workflow in organizations. The authors state that in an atmosphere of trust, managers can conduct SNA surveys and glean information on informal networks in their organizations. Generally, SNA questionnaires should address three different types of social networks in the workplace: (1) the advice network, (2) the trust network, and (3) the communication network (p. 105). People also have to feel safe that their responses to the surveys will not be disseminated widely to their colleagues and that they will not be penalized for their responses. If trust is there, then managers can collect SNA data, cross-check the responses for accuracy, and analyze the information statistically or with SNA software (p. 106).

Krackhardt and Hanson (1993) provide a case study that illustrates just how important it is to ask employees questions about all three networks: advice, trust, and communication. The authors conducted SNA for a computer company with a task force that was experiencing difficulty getting work done. The SNA diagram of advice indicated that the project leader was, in fact, the leader in giving work-related, technical advice. However, the trust SNA showed the project leader to be completely outside the network with only a single link indicating trust from one individual. It was clear from looking at these two SNA diagrams that no one on the team trusted the project leader, and this distrust was the main barrier for getting work done (pp. 106–107). Once this information is captured from SNA, it is imperative that managers know what to do with it. All too often, it is concluded that if an individual lies outside an SNA diagram, he or she is expendable. Since there are three types of social networks in business, and since all workers provide a valuable contribution to the organization with their experience, it is not always the case they these outliers need to be fired. The authors state that managers need to use this information to foster relationships between employees within the information networks that will enable them to make contributions to the company (p. 111). In fact, in the case study provided here, the CEO of the computer company chose an individual who was central to the trust SNA diagram to share responsibility with the current project leader. The two coleads were then able to complete the project and no one had to be removed from the project or fired altogether.

SNA has also been used extensively in various studies on the effect of leadership on team performance. Mehra, Smith, Dixon, and Robertson (2006) state that too much literature is devoted to the study of leadership styles and not enough is dedicated to studying group dynamics when teams consist of more than one leader. They reiterate the fact that many groups consist of informal leaders and these networks are best studied through SNA methodology because it is a relational approach allowing for multiple leaders within a group. SNA also models both vertical (i.e., between formal leader and subordinates) and lateral (among subordinates) leadership within a team.

Mehra et al. (2006) collected sociometric data from a sample of 28 field-based sales teams to investigate how the network structure of leadership perceptions by team members related to team satisfaction and performance (pp. 232–233). They collected extensive data from all members of the field teams, between 6 and 22 individuals, who were each headed by a single formal leader. Team members were given a roster of names from the whole team and asked to rate whom they perceived to be leaders on the team. The teams were then classified as either distributed, teams with more than one leader, or leader-centered teams, those consisting of a single leader. The authors report that distributed leadership does not necessarily lead to greater team performance unless the leaders see themselves and each other as leaders and team members work together. Their study divided the distributed leader networks into distributed-coordinated and distributed-fragmented and found that teams with a distributed-coordinated leadership network had significantly higher performance records than single-leader or distributed-fragmented leadership (p. 241).

Studies in marketing, business, and management are greatly benefiting from the increase in SNA studies in recent years. SNA has been able to shed light on formal and informal social networks, different leadership styles, and their effects on satisfaction and performance in the workplace. Many new research possibilities have been opened up by the important work of the small group of social scientists who use SNA for business studies.

SNA Studies of Childhood

Jeffrey Johnson and Marsha Ironsmith (1994) and colleagues (Johnson et al., 1997) have used SNA to study children and childhood. In 1994, Johnson and Ironsmith provided a literature review on the utility of sociometric studies with children. The literature focuses on the development of peer groups, as well as the child’s place within one, to understand behaviors associated with the peer group and to identify children at risk for social rejection (1994, p. 36). Social rejection in childhood is often later associated with delinquency, mental illness, and poor academic achievement (Roff, Sells, & Golden, 1972; Wentzel & Asher, 1995).

Johnson and Ironsmith’s (1994) work describes issues of reliability, validity, and analyzing group structure and networks over time when utilizing SNA with children. The authors argue that previous sociometric studies with children were largely inadequate because they ignored group structure. Johnson and Ironsmith state that SNA provides a unique opportunity to study the complex social structures and development of young children. SNA has also allowed researchers to identify the influence of cliques and subgroups on the acceptance or rejection of children in their social networks (p. 45). Additionally, Johnson and Ironsmith argue that SNA is useful for measuring changes in the social structure over time.

Johnson et al. (1997) conducted a study with 65 children in a child care center over the course of 3 years. Their methods included sociometric interviews and behavioral observations of the 3- and 4-year-old children. The authors trained the preschool children to use a 3-point “happy face Likert scale” where they were asked how much they like to play with each of the other children. The researchers then read the children a story or gave a short analogies test in order to minimize the chance that the children would discuss the interview with the others. The authors further controlled the validity and reliability of their study by utilizing undergraduate research assistants who were unaware of the hypotheses being tested to conduct the observations. This study found that as children get older, their play preferences are more likely to match their social interactions (p. 402). Johnson et al. also concluded that three of the four cohorts studied had a close correspondence between the results of the interviews and the behavioral observations. Last, the researchers argued that by age 4, the children had stable, organized social networks. Because of this, age 3 is stated to be the ideal time for interventions to minimize the negative effects of social rejection.

Social Networks in Medical Anthropology

Medical anthropologists can use SNA in a variety of ways, such as to evaluate how change happens, to understand why knowledge or meaning is created and its flow (Introcaso, 2005, p. 95), and the key individuals in the complex webs of communities. It is known in psychological, medical, and some SNA research that people are healthier when they experience social relationships with others. It is not just mental health that is better when individuals are connected to others; social support networks improve people’s general health. People encourage each other to engage in preventative health behaviors and provide support for each other when they are ill. In fact, studies have shown that individuals without many social relationships had a death rate 2 to 5 times higher than the individuals who had many social connections (Berkman & Syme, 1979). In addition, social networks contain many important features for medical anthropologists to capture because much initial diagnosis and healing is done in the home or among close friends and community networks. People tend to act as sources of health advice in a number of instances, as described in the following roles:

- People who have long experiences with a particular illness or treatment

- Individuals who have extensive experience of certain life events

- Medical and paramedical professionals and occasionally their spouses

- Organizers of self-help groups

- Clergy members (Helman, 1994, p. 66)

Social networks are important for medical anthropologists to understand because it is often the untrained individuals closest to the patient who are consulted for initial health advice. Pescosolido, Wright, Alegria, and Vera (1998) used SNA to identify patterns of use of mental health services in Puerto Rico. The authors state that a greater emphasis has been placed on the community for developing and supporting mental health initiatives as healthcare reform aims to reduce the levels and duration of care in managed-care settings. Despite this major shift from admittance in a long-term care facility to long-term, community-based care centers, there has been little research conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of this shift (p. 1058). SNA can help understand how the community influences usage of mental health care centers and clinics in Puerto Rico and elsewhere.

Stating that ethnic groups of low socioeconomic status have low rates of mental health care utilization, Pescosolido and colleagues chose to study the relationships of this community in Puerto Rico. The researchers found six main patterns of use in mental health care. This information can be used to identify key players in the community. Armed with this knowledge, agencies can increase education and resources for these key community individuals to help increase mental health care usage, because “knowledge always inextricably combines with action, interactions, and relationships of practice” (Introcaso, 2005, p. 97).

Identifying key players in social networks can also be used for epidemiological studies. Most notable examples of the impact of social relationships and the spread of disease include the black plague in Europe and the spread of smallpox and other European diseases to the Americas (McNeill, 1976). Morris (1994) states that there are three main social systems to investigate with the spread of disease. First, mobile vectors such as rats can spread disease. This allows for widespread infection in a short period of time. Second, there are diseases that require casual or indirect contact, like the measles, that have a relatively short infectious period. Last, there are diseases that are only spread through intimate contact, such as sexually transmitted diseases, that “travel along the most selective forms of social networks” (p. 27). Anthropologists and epidemiologists are beginning to use SNA to identify vectors and new potential victims of sexually transmitted diseases because traditional epidemiological-projection models have proven insufficient.

Network Analyses in Primatology

Social network analysis has not been utilized to its fullest potential with nonhuman primates until relatively recently. Nonhuman primates provide excellent conditions for SNA because they do not have the same symbolic interactions as humans. This makes them a simpler example of social groups that can be studied with SNA (Sade & Dow, 1994, p. 152). Although they may not have the same complexity of symbolic interactions, primates do acquire roles. Primatologists are concerned with understanding these roles, how they are acquired, and their interactions. Roles arise from continual relations of individuals based on age, sex, and dominance—all integral to developing the group’s social structure.

Much pioneering work on understanding nonhuman primate social networks was done by Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey. With this as a foundation, sociograms have been employed in primate studies since the 1960s as anthropologists and primatologists used them as simplified kinship diagrams. Sade (1965) began to utilize sociograms for showing how nonrelated rhesus monkeys form social networks based on grooming behavior. These relational sociograms showed that grooming behavior was much more pronounced among related members of the group than nonrelatives. This research also enabled Sade to recognize how social relationships formed in rhesus groups. Sociograms were also useful for Clark (1985), who published research on the galago contradicting the previous literature, which characterized them as solitary primates. Clark used sociograms to show that while galagos may forage alone, they in fact had social networks that linked individuals of all age and sex classes. Chepko-Sade, Reitz, and Sade later (1989) went beyond the use of sociograms and made predictive models with hierarchical cluster analysis to determine the outcome of a prefission group of rhesus monkeys. Relationships the researches defined as weak had broken completely a year later, resulting in the fissioning of the entire group.

Despite the fact that there is utility in SNA for primatology, Sade and Dow (1994) argue that information is not passed from one individual to a second and to a third, the way information is passed through human groups. However, aggression can be passed down the hierarchy and SNA can identify what that chain will be. Previously, primatologists believed the strongest individuals would “win” these aggression displays. However, SNA has cast doubt on this assumption. Further analysis in the 1970s has shown that the dominance hierarchy plays a more important role in aggression displays than does physical strength (Chase, 1974).

Additionally, primatologists can study social networks not only to understand group structure, but also to appreciate brain research. The neocortex is the outer layer of the cerebral hemispheres that are part of the cerebral cortex. This region of the brain is associated with higher functions such as sensory perception, generation of motor commands, spatial reasoning, conscious thought, and, in humans, language. Neocortex size and group size are strongly correlated in primates because the information-processing capabilities of the neocortex constrain the number of individuals that can coexist (Kudo & Dunbar, 2001). In other words, some primates have a limited ability to store, understand, and process complex social relationships of the group members, resulting in smaller group sizes. Additionally, primates form coalitions, or alliances, that are particularly important and complex features of group dynamics.

Kudo and Dunbar (2001) studied the relationship between coalition size, group size, and neocortex size in 32 species of primates. Their sample included species of prosimians, monkeys, and apes, including humans. The authors used SNA methods and sociograms to identify primary relationships and the total number of relationships in groups. Relationships were defined as grooming partners because all nonhuman primate species engage in this activity to some degree and there is reliable, consistent data collected on grooming patterns for many primate species. Conversational groups were used for the human analysis.

Kudo and Dunbar found that for the majority of species sampled, the mean size of networks is around 75% of the total group size. This means that the majority of individuals are linked together in a single network by a continuous chain of relationships, with a small number of individuals on the periphery. Additionally, the authors state that neocortex size does correlate with the size of grooming cliques, as well as with total group size in many primate species (p. 719). Kudo and Dunbar assert that neocortex size appears to limit group size. The neocortex size may constrain the size of coalitions, or cliques, that animals can maintain for cohesive relationships. Group size seems to be mainly determined by the number of animals that can be incorporated into a single network.

Conclusion

The complex, and often symbolic, interactions between people are what make us distinctly human. As has been shown in the SNA case studies of primate social groups, the nonhuman primates do not even approach the informationsharing social support networks that humans possess. People place much importance on their social relationships, often seeking primary assistance and advice from their social support networks before seeking out professionals. Social scientists recognize the pivotal and central role social relationships play in our daily lives and have developed advanced methods to study these relationships.

Social network analysis is a research methodology developed by social scientists from such diverse fields as psychology, anthropology, and mathematics. The development of SNA took many twists and turns on its long journey to become the methodology that we recognize today. Historically, theoretical frameworks have been attached to SNA, but it is now largely recognized as a set of methods that many researchers and professionals can utilize. This research paper discussed the utility of studying social relationships through SNA, as well as the history and major current uses of SNA in anthropological research. Additional attention has been given to the unique problem of ethical and power issues of SNA research and respondent bias. Last, we concluded with a discussion of diverse anthropological case studies that utilized SNA methodology, such as for nonprofit organizations, childhood social development, medical anthropology, business anthropology, and even primatology.

Of course, there are many other ways in which anthropologists and researchers can utilize SNA. There are also many other methodologies with which to study social relationships. This research paper focused on SNA because of its growing popularity, broad range of utility, and opportunities for development in new directions by anthropologists and social scientists alike.

Bibliography:

- Berkman, L. F., & Syme, S. L. (1979). Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 109(2), 196–204.

- Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2001). Government versus private ownership of public goods. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(4),1343–1372.

- Cartwright, D., & Harary, F. (1956). Structural balance: A generalisation of Heider’s theory. Psychological Review, 63(5), 277–293.

- Chase, I. D., (1974). Models of hierarchy formation in animal societies. Behavioral Science, 19, 374–382.

- Chepko-Sade, B. D., Reitz, K. P., & Sade, D. S. (1989). Patterns of group splitting within matrilineal kinships groups: A study of social group strucutre in Macaca mulatta (cercopithecidae: Primates). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 5, 67–86.

- Clark, A. B. (1985). Sociality in a noctournal “solitary” prosimian: Galago crassicaudatus. International Journal of Primatology, 6, 581–600.

- Fisher, W. F. (1997). Doing good? The politics and antipolitics of NGO practices. Annual Review of Anthropology, 26, 439–464.

- Fowler, A. (1996). Demonstrating NGO performance: Problems and possibilities. Development in Practice, 6, 58–65.

- Gezon, L. L. (2002). Marriage, kin, and compensation: A sociopolitical ecology of gender in Ankarana, Madagascar. Anthropological Quarterly, 7(4), 675–706.

- Helman, C. (1994). Culture, health, and illness (3rd ed.). Newton, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Introcaso, D. M. (2005). The value of social network analysis in health care delivery. New Directions for Evaluation, 107, 95–98.

- Jacobson, D. (1987). The cultural context of social support and support networks. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1(1), 42–67.

- Johnson, J. C., & Ironsmith, M. (1994). Assessing children’s sociometric status: Issues and the application of social network analysis. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama & Sociometry, 47(1), 36–49.

- Johnson, J. C., Ironsmith, M., Whitcher, A. L., Poteat, G. M., Snow, C. W., & Mumford, S. (1997). The development of social networks in preschool children. Early Education and Development, 8(4), 389–405.

- Johnson, J. C., & Orbach, M. K. (2002). Perceiving the political landscape: Ego biases in cognitive political networks. Social Networks, 24, 291–310.

- Killworth, P. D., & Bernard, H. R. (1976). Informant accuracy in social network data. Human Organization 35(3), 269–286.

- Killworth, P. D., & Bernard, H. R. (1980). Informant accuracy in social network data III: A comparison of triadic structure in behavioral and cognitive data. Social Networks, 2, 10–46.

- Krackhardt, D. (1990). Assessing the political landscape: Structure, cognition, and power in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 342–369.

- Krackhardt, D., & Hanson, J. R. (1993, July/August). Informal networks: The company. Harvard Business Review, 104–111.

- Kudo, H., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2001). Neocortex size and social network size in primates. Animal Behavior, 62, 711–722.

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in the social sciences. New York: Harper.

- Lind, A. (2002). Making feminist sense of neoliberalism: The institutionalization of women’s struggles for survival in Ecuador and Bolivia. Willowdale, ON, Canada: De Sitter.

- Mathews, H. F. (2000). Negotiating cultural consensus in a breast cancer self-help group. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 14(3), 394–413.

- McNeill, W. H. (1976). Plagues and peoples. New York: Anchor.

- Mehra, A., Smith, B. R., Dixon, A. L., & Robertson, B. (2006). Distributed leadership in teams: The network of leadership perceptions and team performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 232–245.

- Mills, C. W. (1999). The power elite. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Moreno, J. L. (1934). Who shall survive? New York: Beacon Press.

- Moreno, J. L. (1951). Sociometry, experimental method, and the science of society: An approach to a new political orientation. New York: Beacon House.

- Morris, M. (1994). Epidemiology and social networks: Modeling structured diffusion. In S. Wasserman & J. Galaskiewicz (Eds.), Advances in social network analysis (pp. 26–52). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pescosolido, B., Wright, E. R., Alegria, M., & Vera, M. (1998). Social networks and patterns of use among the poor with mental health problems in Puerto Rico. Medical Care, 36(7), 1057–1072.

- Provan, K. G., & Milward, H. B. (2001). Do networks really work? A framework for evaluating public-sector organizational networks. Public Administration Review, 61, 414–423.

- Riner, R. D. (1981). The supranational network of boards of directors. Current Anthropology, 22, 167–172.

- Roff, M., Sells, S. B., & Golden, M. M. (1972). Social adjustment and personality development in children. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Romney, A. K., & Weller, S. (1984). Predicting informant accuracy from patterns of recall among individuals. Social Networks, 6, 59–78.

- Sade, D. S. (1965). Some aspects of parent-offspring relations in a group of rhesus monkeys, with a discussion of grooming. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 23, 1–17.

- Sade, D. S., & Dow, M. M. (1994). Primate social networks. In S. Wasserman & J. Galaskiewicz (Eds.), Advances in social network analysis (pp. 152–165). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Scott, J. (2000). Social network analysis: A handbook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Stambaugh, M. L. (2008). The seven degrees of Cincinnati: Social networks of social services. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Cincinnati, Ohio.

- Wentzel, K. R., & Asher, S. R. (1995). The academic lives of neglected, rejected, popular, and controversial children. Child Development, 66, 754–763.

- Yeung, K. T. (2005). What does love mean? Exploring network culture in two network settings. Social Forces, 84, 391–420.